Why Moving Costs Can Secretly Wreck Your Taxes (And How to Fix It)

You think moving is just about boxes and truck rentals—until tax season hits. I learned the hard way that relocation expenses can create unexpected red flags with tax authorities. What seemed like routine costs suddenly became audit risks. This isn’t just about saving receipts; it’s about staying compliant while protecting your wallet. If you’ve ever moved for a job, downsized, or relocated across state lines, what you don’t know could cost you. The financial ripple effects of a move often go unnoticed until a tax return raises questions. This article reveals how seemingly small decisions during a relocation can have long-term tax consequences—and how to navigate them wisely.

The Hidden Tax Trap in Your Move

Moving is often seen as a logistical challenge, not a financial one. Yet behind the scenes, tax implications quietly accumulate. Many people assume that all moving expenses are personal and therefore non-deductible, which is mostly true under current tax law. However, the way a move is structured—especially if tied to employment, property transfer, or business operations—can create taxable events that go unnoticed until audit time. For example, when an employer reimburses moving costs, those payments are generally considered taxable income for the employee. This shift, introduced by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, eliminated most moving deductions for private-sector workers but did not eliminate reporting requirements. As a result, what once seemed like a tax-neutral benefit now triggers income reporting and potential liability.

The IRS pays particular attention when assets change location or ownership, especially if they cross state lines. A move involving the sale of a primary residence, for instance, may trigger capital gains tax if the homeowner does not meet the exclusion criteria—namely, owning and living in the home for at least two of the past five years. While most homeowners qualify for up to $250,000 in tax-free gains ($500,000 for married couples), those who sell quickly due to relocation may fall short of the requirement. This creates a hidden tax liability that can catch taxpayers off guard. Additionally, transferring vehicles, boats, or investment properties across state borders can trigger registration fees, use taxes, or even gift tax implications if assets are reassigned within a family.

Another often-overlooked issue involves home improvements made just before a move. While upgrades like a new roof or kitchen remodel increase a home’s value, they also affect the cost basis when the property sells. If these improvements are not properly documented, taxpayers may overpay capital gains tax due to an understated basis. Similarly, moving expenses related to a home office—especially for self-employed individuals—must be carefully evaluated. If the home office was claimed as a deduction, closing it upon relocation requires adjustments to depreciation recapture rules, which can lead to additional taxable income. These are not obscure loopholes but real, enforceable parts of tax law that apply to ordinary people making ordinary life decisions.

What makes this trap so dangerous is its invisibility. Most families don’t consult a tax advisor before packing boxes. They rely on moving checklists, real estate agents, and online guides—none of which typically emphasize tax compliance. As a result, well-intentioned actions—like letting a child drive a car registered in another state or failing to update voter registration—can be interpreted by tax authorities as signs of unresolved residency or unreported income. The key takeaway is that every relocation decision has a financial footprint. Understanding this early allows families to avoid costly surprises and maintain full compliance without sacrificing peace of mind.

When a Move Becomes a Taxable Event

Not all moves carry the same tax weight. The IRS distinguishes between personal relocations and job-related moves, and the difference can determine whether certain expenses are reportable or deductible. For most taxpayers, a move for personal reasons—such as being closer to family or retiring to a warmer climate—has no direct tax consequences beyond potential state residency changes. However, when a move is tied to employment, the rules become more complex. Prior to 2018, employees could deduct certain moving expenses if they met distance and time tests. Today, only active-duty military members relocating under orders can claim such deductions. For everyone else, employer-paid moving costs are treated as taxable compensation.

This means that if your company pays for your moving truck, temporary housing, or travel expenses, those amounts appear on your W-2 form as wages. They are subject to federal income tax, Social Security, and Medicare taxes—just like a bonus. While this may seem like a minor adjustment, it can push a taxpayer into a higher bracket or affect eligibility for certain credits, such as the Child Tax Credit or Earned Income Tax Credit. For example, a $10,000 reimbursement could increase taxable income enough to reduce or eliminate credit eligibility, costing hundreds or even thousands in lost benefits. This indirect impact is rarely explained during relocation planning, leaving families financially exposed.

Selling a home before or after a move is another common taxable event. While the IRS allows exclusion of up to $250,000 in capital gains for single filers, this benefit hinges on meeting ownership and use tests. Taxpayers who relocate due to job changes, health issues, or family needs may not satisfy the two-year residency rule. In such cases, partial exclusions may apply, but only if the move was due to specific qualifying reasons such as employment, health, or unforeseen circumstances. Without proper documentation, even legitimate hardships may not be recognized by the IRS. This underscores the importance of keeping records—such as job offer letters, medical reports, or lease terminations—that support the timing and necessity of the move.

Vehicle transfers also present hidden tax risks. When moving to a new state, registering a car often involves paying sales or use tax based on the vehicle’s current value. Some states, like Virginia and Indiana, impose a one-time tax on incoming vehicles. Others, like California, assess value based on the purchase price and depreciation. Failing to register promptly or attempting to delay registration to avoid taxes can result in penalties and interest. Additionally, gifting a vehicle to a family member during a move—such as letting a college student keep a car in a different state—may trigger gift tax reporting if the value exceeds the annual exclusion amount. While no tax is typically due unless lifetime limits are exceeded, the reporting requirement itself creates administrative burden and potential scrutiny.

Deductions That Still Work (If You Do It Right)

Despite the narrowing of moving-related tax breaks, opportunities still exist for those who qualify. The most significant exception applies to active-duty military personnel who relocate due to permanent change of station (PCS) orders. These individuals can deduct a wide range of expenses, including transportation, lodging, packing, storage, and even temporary home insurance. Unlike civilian deductions before 2018, military moving deductions do not require itemizing and can be claimed directly on Form 3903. This provision recognizes the unique nature of military service, where relocations are frequent and outside the individual’s control.

Self-employed individuals and small business owners may also find tax advantages in a move, though not through direct moving expense deductions. Instead, they can benefit from strategic business decisions made during relocation. For example, setting up a new home office in the destination home allows for ongoing deductions of mortgage interest, utilities, and insurance—provided the space is used regularly and exclusively for business. If the previous home office was depreciated, the taxpayer must account for depreciation recapture upon sale of the old home, but careful planning can minimize this impact. Additionally, business-related travel during the move—such as scouting locations or meeting clients—may be deductible as ordinary and necessary business expenses.

Another often-overlooked opportunity involves timing. While moving expenses themselves are not deductible for most, the timing of a home sale and purchase can influence capital gains treatment. Homeowners who move due to job changes, health issues, or multiple births may qualify for a reduced ownership period under IRS Rule 152. This allows partial exclusion of capital gains even if the two-year test isn’t fully met. To claim this, taxpayers must document the reason for the shortened ownership and calculate the allowable exclusion based on the proportion of time lived in the home. Proper recordkeeping is essential: bank statements, employment records, and medical bills can all serve as supporting evidence.

For those relocating for work, certain unreimbursed employee expenses may still be claimed under specific circumstances, though these are limited. If an employee is required to pay for relocation costs upfront and is later reimbursed through a non-accountable plan, the reimbursement is taxable, but the original expense may not be deductible. However, if the move is part of starting a new business or joining a partnership, some costs may be treated as startup expenses and amortized over 15 years. These include legal fees, travel for site selection, and market research. While not immediate deductions, they provide long-term tax relief and should be tracked carefully. The key is understanding eligibility and maintaining meticulous documentation to support every claim.

State Tax Lines Blur During Relocations

Crossing a state border transforms a simple move into a multi-jurisdictional tax event. Each state has its own rules for determining tax residency, and failing to comply can result in dual tax liability. Most states define residency based on physical presence and intent. Living in a state for more than 183 days typically triggers residency, but other factors—such as voter registration, driver’s license, property ownership, and bank accounts—also matter. A taxpayer who moves from New York to Florida, for example, must not only establish residency in Florida but also sever ties with New York to avoid being considered a resident for part of the year.

This becomes especially critical for high-income earners. States like California, New Jersey, and New York are known for aggressively pursuing former residents who maintain financial or familial connections. The so-called “jock tax” allows these states to tax non-residents on income earned within their borders, but they also scrutinize whether individuals have truly left. For instance, keeping a vacation home, allowing children to attend public schools, or maintaining a business presence can all be used as evidence of continued residency. In some cases, taxpayers have been audited years after moving and forced to pay back taxes, interest, and penalties.

Dual residency can also arise when spouses work in different states or when one spouse moves ahead of the family. In such cases, states may require part-year or non-resident filings, complicating tax preparation. Withholding from paychecks may not reflect the correct state, leading to underpayment or overpayment. Coordinating W-4 forms, updating payroll settings, and making estimated tax payments can help manage this transition. Additionally, some states have reciprocal agreements that prevent double taxation for commuters, but these apply only to specific state pairs and do not cover all types of income.

Establishing domicile requires more than just a change of address. It involves updating legal documents, registering to vote, obtaining a new driver’s license, and closing local accounts. Doing so promptly creates a clear paper trail that supports residency claims. Digital footprints—such as utility bills, internet service, and streaming subscriptions—also play a role. Tax authorities increasingly use data analytics to detect inconsistencies, such as a claimed Florida residency paired with frequent New York credit card transactions. To avoid disputes, families should treat residency establishment as a formal process, not an afterthought. This level of diligence protects against audits and ensures compliance across state lines.

Risk Control: Avoiding Audits and Penalties

Tax compliance during relocation is not just about saving money—it’s about reducing exposure. The IRS and state agencies use automated systems to flag inconsistencies, and moving-related transactions often stand out. Large deductions without documentation, mismatched employer reports, or sudden changes in residency can all trigger audits. The best defense is a well-organized, transparent record. Creating a dedicated tax relocation file at the start of the move process allows families to collect and categorize every relevant document. This includes receipts for moving services, mileage logs, temporary housing invoices, and copies of job offer letters or military orders.

Digital tools can enhance accuracy and accessibility. Mobile apps that scan and store receipts, cloud-based folders with date-stamped entries, and GPS mileage trackers all contribute to a defensible paper trail. These tools are especially useful for self-employed individuals or those with complex moves involving multiple locations. For example, a consultant who works remotely may need to prove where business activities occurred during a transition period. Without contemporaneous records, it becomes difficult to substantiate claims or refute audit allegations.

Another major red flag is the failure to report employer reimbursements. Since these are taxable, omitting them from income is considered underreporting—a common audit trigger. Employers report these amounts on Form W-2, so any discrepancy between the W-2 and the tax return raises suspicion. Similarly, claiming deductions without meeting eligibility criteria—such as the distance test for military moves—can lead to disallowed claims and penalties. The IRS imposes accuracy-related penalties of 20% on underpayments due to negligence or substantial understatement of tax.

Consulting a tax professional before filing is one of the most effective risk control measures. A CPA or enrolled agent can review the move’s financial aspects, identify potential issues, and ensure proper reporting. This is especially valuable for cross-state moves, home sales, or business-related relocations. Early consultation allows time to gather missing documents, correct errors, and make strategic decisions—such as adjusting withholding or making estimated payments. The cost of professional advice is often far less than the cost of an audit, making it a wise investment in financial security.

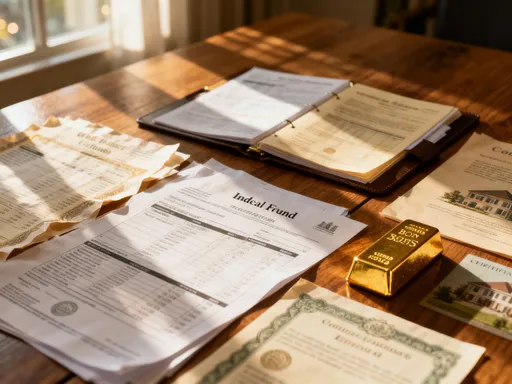

Smart Moves That Save Money Long-Term

Beyond avoiding penalties, strategic planning turns relocation into a financial opportunity. Timing the move within the tax year can influence eligibility for credits and deductions. For example, moving early in the year allows more time to establish residency and align payroll withholding. Conversely, delaying a home sale until after the two-year ownership mark can preserve capital gains exclusion. Families should coordinate major transactions—such as selling a home, buying a new one, or starting a business—around tax deadlines to maximize benefits.

For those with investment properties, a 1031 exchange offers a powerful tool. By reinvesting proceeds from a sold property into a like-kind replacement, taxpayers can defer capital gains tax indefinitely. While this applies primarily to rental or business properties, it can be part of a broader relocation strategy. For instance, a family moving from a high-cost to a low-cost state might sell a rental property and use the funds to purchase a new one in the destination state, deferring taxes while improving cash flow. This requires strict adherence to timelines and rules, but the long-term savings can be substantial.

Adjusting retirement account withdrawals during a transition year can also reduce tax liability. Moving often creates a temporary drop in income, especially if there’s a gap between jobs. This presents an opportunity to take taxable withdrawals from traditional IRAs or 401(k)s at a lower tax rate. Converting some funds to a Roth IRA during this period can lock in lower rates and provide tax-free growth in retirement. This strategy, known as “tax bracket arbitrage,” requires careful planning but can yield lasting benefits.

Additionally, relocating to a state with no income tax—such as Florida, Texas, or Tennessee—can reduce long-term tax burden. While federal taxes remain unchanged, eliminating state income tax improves disposable income and investment returns. However, this benefit only materializes if residency is properly established. Families must avoid maintaining significant ties to high-tax states, as doing so can lead to costly disputes. The goal is not tax avoidance, which is illegal, but tax efficiency, which is smart financial planning.

Building a Tax-Smart Relocation Plan

The most effective way to manage the financial impact of a move is through proactive planning. Every relocation should begin with a tax assessment that considers employment status, property ownership, and destination state rules. Families should ask key questions: Will the move affect my residency? Are there capital gains implications from selling my home? Will employer reimbursements increase my taxable income? Answering these early allows for informed decisions and reduces last-minute surprises.

Consulting a tax advisor before the move is a critical step. A professional can help structure the relocation to minimize tax exposure, identify eligible deductions, and ensure compliance with both federal and state laws. They can also assist with updating legal documents, such as wills, trusts, and powers of attorney, to reflect the new jurisdiction. These documents may have tax implications, especially if they involve asset transfers or estate planning.

Creating a checklist that includes tax-related tasks—such as updating the IRS with a new address, notifying state tax agencies, and transferring vehicle registration—helps maintain continuity. Digital tools can automate reminders and track deadlines. Families should also review their insurance policies, as moving may affect home, auto, and liability coverage. Some insurers offer discounts for bundling or loyalty, while others adjust premiums based on location.

In the end, a move should not be a financial setback but a strategic step toward greater stability. With careful planning, families can protect their wealth, comply with tax laws, and gain peace of mind. The goal is not to exploit loopholes but to navigate the system wisely. By treating relocation as both a logistical and financial event, households can turn a stressful life change into a foundation for long-term prosperity.