Why Your Legacy Plan Needs Smarter Tax Moves—A Deep Dive

What if the wealth you’ve built could shrink by half before reaching your family? I’ve seen it happen—hard-earned assets eroded by overlooked tax traps in estate planning. It’s not just about having a will; it’s about strategy. In this piece, we’ll explore how smart, proactive tax planning can protect what you leave behind. Think of it as armor for your legacy—because passing on wealth shouldn’t mean surrendering it to avoidable taxes. Many people assume that writing a will is enough to ensure their family inherits what they’ve worked for. But without a deeper understanding of tax implications, even the most carefully drafted documents may fail to deliver. The reality is that estate and inheritance taxes, capital gains rules, and liquidity issues can quietly drain value from an estate, sometimes leaving heirs with far less than expected. This article is designed to help you see beyond the basics and take control of the financial details that truly shape a lasting legacy.

The Hidden Cost of Passing On Wealth

Transferring wealth at the end of life is often viewed as a simple act of love or duty, but it is also a significant financial transaction—one that comes with hidden costs. While emotions guide many decisions in estate planning, taxes operate without sentiment. Without deliberate action, a large portion of an estate can be lost to various forms of taxation before a single heir receives anything. These losses are not the result of malice or complexity alone, but of misunderstanding and inaction. The most common culprits are estate taxes, inheritance taxes, and capital gains taxes, each of which applies under different circumstances and in varying degrees depending on location and structure.

Estate taxes are imposed on the total value of a person’s assets at the time of death. In some jurisdictions, such as certain states in the United States, these taxes apply even if the federal government does not levy one. The threshold for taxation varies, and while many assume their estate falls below the limit, appreciation in property, investment accounts, or business interests can push the total value into taxable territory. Inheritance taxes, on the other hand, are paid by the recipient rather than the estate itself, and their rates often depend on the relationship between the giver and the heir. For example, spouses may be exempt, while more distant relatives face higher rates. These distinctions matter greatly when designing a distribution plan.

Another often-overlooked cost arises when inherited assets are later sold. Capital gains tax applies to the increase in value of an asset from its original purchase price to its sale price. If an heir sells stock or real estate that has appreciated over decades, they could face a substantial tax bill—unless the cost basis has been adjusted properly. This is where the step-up in basis rule becomes critical, a topic explored in detail later. The key takeaway here is that taxes do not disappear just because wealth is passed down; they may simply be delayed or misallocated. The difference between a well-protected estate and one that diminishes significantly lies in foresight and planning.

Reactive planning—waiting until a crisis or death to act—exposes families to avoidable risks. By contrast, proactive strategies allow individuals to shape outcomes while they still have control. This includes evaluating asset types, understanding tax thresholds, and anticipating future liabilities. The goal is not to eliminate taxes entirely—this is neither realistic nor legal—but to minimize their impact through lawful and structured approaches. Every dollar preserved through smart planning is a dollar that remains within the family, supporting education, homeownership, or future generations. The hidden cost of passing on wealth is not inevitable. With awareness and action, it can be managed, reduced, and in many cases, prevented altogether.

How Tax Systems Treat Inherited Assets

Tax treatment of inherited assets varies widely across countries, and even within regions of the same country. There is no universal system, which means that individuals with assets in multiple locations must navigate a patchwork of rules. Some nations impose steep estate taxes, while others rely on inheritance taxes paid by beneficiaries. Still others use capital gains taxation as the primary mechanism for collecting revenue from wealth transfers. Understanding how these systems work is essential for anyone who wants to pass on wealth efficiently and fairly.

In the United States, the federal estate tax applies to estates exceeding a certain exemption amount, which is periodically adjusted for inflation. As of recent years, this threshold has been high enough that only a small percentage of estates are affected at the federal level. However, several states impose their own estate or inheritance taxes with lower thresholds, meaning that residency or property ownership can trigger liability even if the federal tax does not apply. For example, owning a vacation home in a state with an inheritance tax could expose heirs to tax obligations based on that single asset. This highlights the importance of location-specific planning.

In contrast, countries like the United Kingdom impose inheritance tax on estates above a certain value, with certain exemptions for spouses and charitable donations. The rate is applied to the amount exceeding the threshold, and there are reliefs available for family-owned businesses or agricultural property. Meanwhile, nations such as Canada do not have a formal estate or inheritance tax, but they do tax capital gains on most assets at the time of death, treating the deceased as having sold all non-registered assets at fair market value. This deemed disposition rule can result in a large tax bill, even if no actual sale occurs. The tax is paid by the estate, and if insufficient liquidity exists, assets may need to be sold to cover the liability.

Other jurisdictions, such as Australia and New Zealand, have abolished inheritance and estate taxes entirely, relying instead on income and capital gains taxes in other contexts. However, this does not mean that wealth transfers are tax-free. Gifting rules, superannuation payouts, and family trust structures still carry tax implications. In many European countries, including France and Germany, inheritance taxes are progressive and vary based on the heir’s relationship to the deceased. Closer relatives typically face lower rates, while distant relatives or unrelated individuals may pay significantly more.

One of the most important yet frequently misunderstood aspects of international estate planning is the potential for double taxation. A person who holds assets in multiple countries may find that more than one government claims a right to tax the same transfer. Tax treaties between nations can help mitigate this risk, but they require careful coordination and documentation. Without proper planning, heirs could face unexpected bills that erode the value of what they inherit. The lesson is clear: assumptions about tax treatment can be costly. A thorough review of applicable laws, combined with professional advice, is necessary to ensure that wealth is transferred in the most efficient way possible.

Gifting Strategies: Reducing the Taxable Estate

One of the most effective ways to reduce the size of a taxable estate is through lifetime gifting. Rather than waiting until death to transfer wealth, individuals can gradually shift assets to heirs while they are still alive. This approach offers several advantages: it reduces the total value of the estate subject to taxation, allows the giver to witness the impact of their generosity, and can help younger generations build financial stability earlier in life. When structured correctly, gifting is not just a personal decision but a strategic financial move.

Most tax systems provide annual gift exclusions that allow individuals to transfer a certain amount of money or assets each year without triggering gift tax. In the United States, for example, this exclusion is adjusted periodically and can be used per recipient. This means a person can give the maximum amount to multiple children, grandchildren, or others without incurring tax liability. Married couples may also combine their exclusions, effectively doubling the annual transfer limit. Over time, these gifts can significantly reduce the size of an estate, lowering potential tax exposure when the time comes to settle the final account.

Beyond annual exclusions, many countries offer lifetime gift exemptions or unified credit systems that allow larger transfers over time. These can be used strategically to move appreciating assets—such as stocks or real estate—out of the estate before their value increases further. By doing so, not only is the current value removed from the estate, but all future growth occurs outside of it, potentially saving substantial taxes. However, this benefit must be weighed against the loss of control and the possibility of needing those resources later in life.

Another valuable gifting technique involves direct payments for education or medical expenses. In several jurisdictions, these payments are exempt from gift tax regardless of amount, as long as they are made directly to the institution or provider. This allows individuals to support loved ones in meaningful ways—such as paying for college tuition or covering healthcare costs—without using up their annual or lifetime exemptions. It’s a powerful tool for families who want to assist younger members without triggering tax consequences.

Despite its benefits, gifting is not without risks. Poorly timed or structured gifts can lead to unintended outcomes. For example, transferring a family home too early may disqualify the giver from certain tax benefits or Medicaid eligibility. Large gifts may also create friction among siblings if perceived as unequal. Additionally, in some countries, gifts made within a certain number of years before death may still be included in the taxable estate, undermining the intended tax savings. Therefore, gifting should be part of a broader plan, not an isolated action. Consulting with tax and legal advisors ensures that each transfer aligns with both financial goals and family dynamics.

Trusts as Tax-Efficient Vehicles

Trusts are among the most powerful tools available for managing wealth transfer and minimizing tax liability. Far more than simple legal documents, they serve as structured frameworks that can protect assets, control distribution, and provide tax advantages. When properly designed, a trust can operate independently of the probate process, allowing for faster and more private transfer of wealth. More importantly, certain types of trusts offer significant tax benefits that can preserve value across generations.

There are two main categories of trusts: revocable and irrevocable. A revocable trust allows the creator—also known as the grantor—to retain control over the assets during their lifetime, including the ability to modify or dissolve the trust. While this offers flexibility, it does not remove assets from the taxable estate, meaning they may still be subject to estate taxes. An irrevocable trust, on the other hand, transfers ownership permanently. Once assets are placed inside, they are no longer considered part of the grantor’s estate, which can reduce or eliminate estate tax liability. This makes irrevocable trusts particularly valuable for individuals with large estates.

One specialized type of irrevocable trust is the irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT). Life insurance proceeds are typically included in the taxable estate if the policy is owned by the deceased. By placing the policy inside an ILIT, the death benefit is excluded from the estate, allowing heirs to receive the full payout without tax erosion. This is especially useful for covering expected estate tax bills, ensuring that other assets do not need to be liquidated to pay the government. Another example is the dynasty trust, which is designed to last for multiple generations. By leveraging generation-skipping transfer tax exemptions, these trusts can pass wealth from grandparents to grandchildren—or beyond—without incurring taxes at each level.

Trusts also offer control over how and when beneficiaries receive assets. A parent may want to ensure that children do not receive large sums all at once, instead releasing funds at certain ages or milestones. This protects against poor financial decisions and supports long-term stability. Additionally, trusts can include provisions for special needs beneficiaries, ensuring access to inheritance without jeopardizing government benefits.

Despite their advantages, trusts are not without complexity. Improper drafting, funding, or administration can invalidate their benefits or trigger unintended taxes. For example, failing to retitle assets into the name of the trust means they remain outside its protection. Similarly, missteps in trustee selection or distribution rules can lead to disputes or legal challenges. Because of these risks, establishing a trust should always involve experienced legal and tax professionals. When done correctly, however, a trust becomes more than a tax tool—it becomes a cornerstone of a lasting legacy.

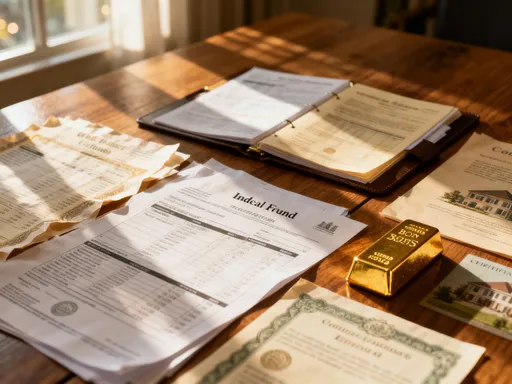

Step-Up in Basis: A Critical Detail Often Ignored

One of the most powerful yet underutilized benefits in estate planning is the step-up in basis. This tax rule can significantly reduce or even eliminate capital gains taxes when heirs sell inherited assets. Despite its importance, many families overlook it, often making decisions—such as gifting assets during life—that inadvertently forfeit this advantage. Understanding how the step-up works is essential for preserving wealth across generations.

The concept is straightforward: when a person inherits an asset such as stocks, real estate, or mutual funds, the cost basis—the original purchase price used to calculate capital gains—is adjusted to the market value at the time of the original owner’s death. For example, if someone bought stock decades ago for $10,000 and it is worth $100,000 at the time of death, the heir’s cost basis becomes $100,000. If they later sell it for $105,000, they only pay capital gains tax on $5,000, not the full $95,000 of appreciation. Without the step-up, the heir would owe tax on the entire gain, potentially leading to a much larger bill.

This rule applies in many countries, including the United States, and covers a wide range of assets. It is particularly valuable for real estate, which often appreciates significantly over time. A family home passed to children may have been purchased for a fraction of its current value. Thanks to the step-up, the children can sell it without paying tax on decades of growth. This benefit is automatic in most cases, requiring no special filing, but only if the asset is transferred at death.

The danger arises when individuals choose to gift assets before death. While this may seem like a way to reduce the estate, it eliminates the step-up in basis. If the same stock is gifted while the owner is alive, the heir inherits the original $10,000 basis. Selling it later for $105,000 triggers capital gains tax on $95,000. This single decision could cost tens of thousands in avoidable taxes. The same principle applies to real estate, business interests, and other appreciating assets.

Strategic planning involves deciding which assets to pass at death and which to gift during life. Assets with low appreciation or high cost basis may be better candidates for gifting, while highly appreciated assets should typically be held until death to maximize the step-up benefit. This requires careful coordination and documentation, but the payoff can be substantial. The step-up in basis is not a loophole—it is a legitimate tax provision designed to ease the transition of wealth. Those who understand and use it wisely ensure that more of their legacy stays in the family, not in government coffers.

Balancing Liquidity and Tax Efficiency

Even the most sophisticated estate plan can fail if it lacks liquidity. When estate taxes are due, they must be paid in cash—often within nine months of death. For families holding significant wealth in illiquid assets such as real estate, private businesses, or collectibles, this deadline can create a crisis. Without ready access to cash, heirs may be forced to sell assets quickly, sometimes at a loss, just to cover the tax bill. This fire sale not only reduces the value of the estate but can disrupt family businesses or displace long-held properties.

Liquidity planning is therefore a critical component of tax-efficient wealth transfer. It involves ensuring that sufficient cash or easily convertible assets are available to meet tax obligations without disrupting the core structure of the estate. One common solution is life insurance. A permanent life insurance policy, especially when held within an irrevocable life insurance trust, can provide a tax-free death benefit that matches the expected tax liability. This allows the estate to remain intact while fulfilling its financial duties.

Another approach is to maintain a portion of the portfolio in liquid investments such as money market funds, bonds, or dividend-paying stocks. These can be sold or drawn upon without affecting major assets. For business owners, buy-sell agreements funded with life insurance can ensure that ownership transitions smoothly while providing cash to the estate. These agreements specify how shares will be valued and purchased upon death, preventing disputes and ensuring liquidity.

Tax efficiency and liquidity must be balanced carefully. Holding too much cash can reduce overall returns, while holding too little increases risk. The ideal structure depends on the size of the estate, the nature of its assets, and the tax environment. A family with a $5 million estate consisting mostly of real estate in a high-tax state will have different needs than one with diversified investments and lower exposure. The key is to anticipate obligations and prepare in advance.

Proper liquidity planning also supports family harmony. When taxes are paid without forced sales, heirs can focus on honoring the legacy rather than managing a financial emergency. It allows time to make thoughtful decisions about whether to keep, sell, or restructure inherited assets. This stability is especially important for younger beneficiaries who may lack experience in financial management. By addressing liquidity early, families protect not just wealth, but peace of mind.

Working With Advisors: Building a Coordinated Team

No single professional can manage all aspects of tax-smart legacy planning. It requires a coordinated team of experts, each bringing specialized knowledge to the table. Estate attorneys draft wills and trusts, tax professionals calculate liabilities and identify savings, and financial advisors align investment strategies with long-term goals. When these roles work in isolation, gaps emerge. When they collaborate, the result is a unified, resilient plan that reflects both legal precision and financial wisdom.

Choosing the right advisors begins with identifying credentials and experience. Look for certified public accountants (CPAs) with expertise in estate taxation, attorneys licensed in your state with a focus on estate planning, and financial advisors who hold designations such as CFP (Certified Financial Planner). Equally important is their willingness to communicate with one another. Some clients appoint a lead advisor to coordinate meetings and ensure alignment. Others use secure platforms to share documents and updates. The goal is integration, not silos.

Effective collaboration means asking the right questions. Does the trust structure support the tax strategy? Will gifting now trigger unintended consequences? How will changes in tax law affect the plan? Advisors should be able to explain complex topics in clear terms and offer realistic projections. They should also review the plan regularly, especially after major life events such as marriage, birth, or changes in net worth.

Building trust with advisors takes time, but it is worth the effort. A good team does more than complete paperwork—they challenge assumptions, offer alternatives, and help families think ahead. They recognize that legacy planning is not just about numbers, but about values, relationships, and long-term security. By working together, they turn intention into action, ensuring that wealth serves its highest purpose: supporting future generations with dignity and care.

Passing on wealth is about more than money—it’s about legacy, values, and care for those who come after. But sentiment alone won’t shield assets from tax erosion. A thoughtful, informed approach to tax planning turns intention into impact. By understanding the rules, using the right tools, and seeking expert guidance, you can ensure your hard-earned wealth supports your family for generations—not the tax authorities.